by Faith Antion

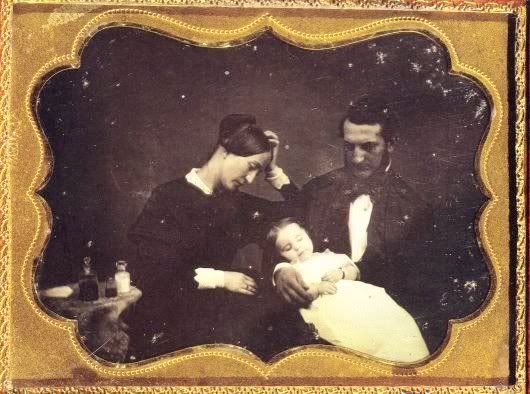

It keeps making its way to the surface, these days, some or other configuration of the idea that our sympathies can be gained (as viewers, as readers, as spectators in the world) when we sense a kind of transfiguration or threat to the human body.

I touched on it weeks ago, when I tried to suggest to my students that part of what's at work in Dorothea Lange's photos of migrant farmers (at least for me) is the immediate queasiness I feel when I see another person's bare feet in dusty dirt. I can't help myself - my throat instantly constricts and I grab the nearest glass of water, the closest bottle of lotion.

by Dorothea Lange

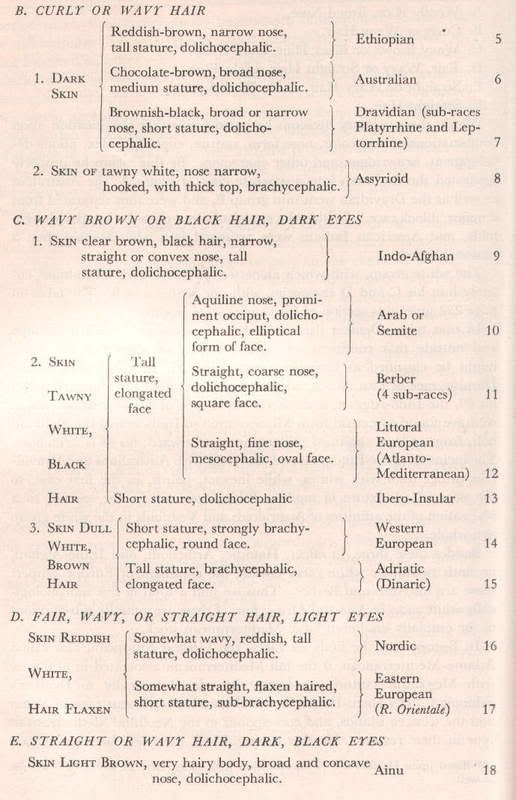

It reared its head again, this idea, as we were discussing an excerpt of Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes. In it, Barthes starts to investigate the structural elements of several photographs from rebellion-torn Nicaragua. I decided I wanted to find out what would happen if the students looked at a long series of photographs of their choosing. For whatever reason, a bunch of the students ended up looking at photos of people with deformities - a child with its brain encased in a thin membrane that is an outgrowth of its scull, children with limbs that grew backwards, men so emaciated by Chernobyl-induced cancer that the students wondered if what they saw was a trick of the camera. We wanted to, or at least I wanted them to, establish a system that would account for the responses we feel to bodies in pain (even as I write this I'm aware of the complexities of creating such a system, of manufacturing such a "we").

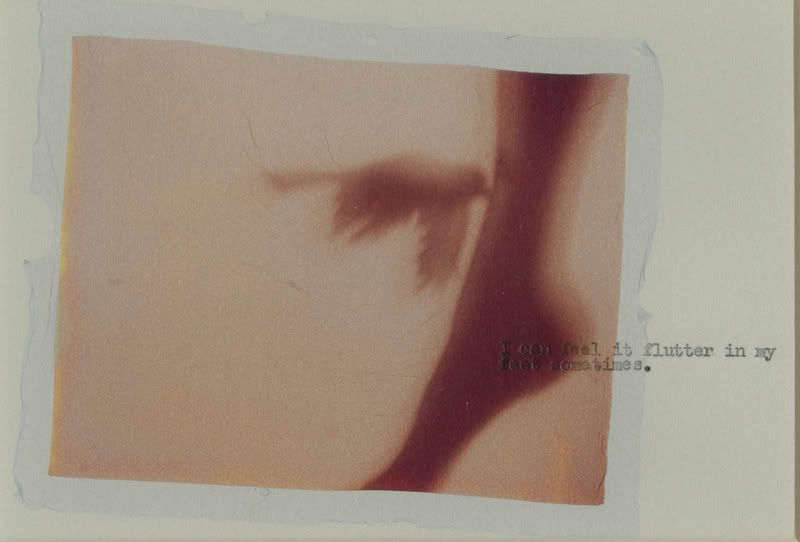

Kooza contortionists - where do their organs go?

I think there's something to the idea that when we combine the sympathy we feel for other human bodies with the threat of injury we imagine to our own that results in a very compelling kind of fascination and repulsion.

• • •

As a note (I wonder if this is at all interesting), this post has been sitting in my drafts for days and days, weeks, really. I've really struggled to let it go because it feels unfinished. There's a lot I still want to say about regarding other people's pain or potential pain that I can't quite properly verbalize at this point. But I've decided just to relinquish this post. What the hell - it's a blog; I can always come back to the idea again later.