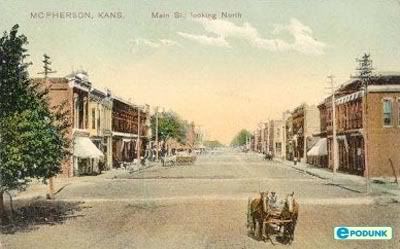

Aaron grew up in the exact center of Kansas, which, he is fond of saying, is the exact center of the continental United States. As a boy he was so sure of this that he imagined the President sent two planes careening across the country on the Fourth of July to cross paths over McPherson ("there's no fear in McPherson"), Kansas, their grey plumes superimposing on the map an X. McPherson, in some ways, is not unlike Storrs. It has a somewhat awkward combination of rural and suburban areas. It has a small college in the town and is nestled among Wichita, Topeka, Hutchinson, and some other Kansan cities. In other ways, of course, it is drastically different.

Aaron was raised by, quite possibly, the only couple with leftist leanings in the entire town. Let us not forget, Kansas is a red state (a fact that caused me no small amount of anxiety upon my first trip there). Had I known, at the time, what I know now, I would not have been so anxious. The conservatives in McPherson are not nearly so confrontational as those who are members of my extended family. (Or, at least, I can't see the ways in which they're confrontational.) He was, although in many ways privileged—upper middle class, white, male, able bodied, intelligent—part of a minority. I wonder (I have not asked) to what degree he hid or tried to streamline his parents' beliefs while growing up. In some ways, he needn't have tried very hard: his father and grandfather and aunt were all part of the town's most prestigious law firm. His uncle was a very successful business man. There is a certain amount of prosperity and small town history associated with the Bremyers. That should have shielded some of the eccentricities of his nuclear family.

But let me put the easy difference of politics aside for a moment. The thing that surprised me most, that pricked me to attention, was the degree to which I was made uncomfortable by the friendly, familiar greetings of strangers. Aaron and I would be driving around town and the overweight man mowing his lawn would pause, wipe the sweat from his brow (depositing some grass clippings and, one imagines, some chiggers), squint his eyes, and wave. "Do you know him?" I asked, brow pursed, trying to hide, somewhat from the mowing man. No, he didn't. That's just what they do there. They say hello to people they don't even know. Even when they're all sweating and in the midst of less than pleasant chores.

My heart was pounding in my ears. I couldn't even look Aaron in the eye. What was going on? I looked down at my hands to see that I was madly clutching at the skin between my left index finger and thumb. I looked past my hands to see that my legs were pressed, firmly, together. Why was I having such a strong reaction to this small act? I let it pass.

But the greetings continued. Walking down Main Street, people he didn't know said hello (and he responded with apparent reciprocation of their enthusiasm). We went for a stroll around the park near his aunt and uncle's home. I looked up. About 100 feet away a person was walking in the opposite direction, toward us. I trained my eyes back down on my feet. "Come on, Megh. Say hello to the person," Aaron said to me. I was grinding my teeth and I had started to hold my breath. "I'll try," I muttered. I looked up, offered my most stoic and salty New England nod of the head acknowledgement, and mouthed the syllables "hello." I tried.

I thought about it, a lot, that night in bed. I tried to recall people who had said hello to me like that, who had waved. There was the old (octogenarian) blind man who used to sit on the stone wall in front of his house by the road and wave his cane at passing cars. There were the drunk men I would sometimes encounter in bars as a child, sipping on my Shirley Temples. There were the down and outs in Willimantic who would try to par out advice to little girls. There was the occasional very old person, who more often than not would say "God bless you," not hello. But I always thought they were up to something. There was the Viet Nam vet who had always struck me as shell shocked; he walked the streets around campus and would, shaking, wave his walking stick at passing cars. There were the letches.

But it isn't standard practice in New England to greet someone with whom you're not acquainted. Even with acquaintances, more often than not a nod of the head will do; no need to stop what you're doing and have a conversation. It seems to me that New Englanders tend to foster this illusion of isolation, of privacy. When someone threatens that illusion by being too forthcoming with unsolicited conversation, we tend to read the behavior as, well, crazy (or, at the very least, highly exceptional). We look on it as very suspect.

I'm not entirely sure why this is the case. I have a couple theories, though. (Aaron used to always be amused by the theories my family tends to come up for things, and then present as hard and fast beliefs. They rarely are the result of any kind of authority on a given topic. In other words, we're a family of hucksters, we're bullshitters.) A possibility: New Englanders, historically, are predisposed to a certain degree of austerity. Given our propensity for being alone and working or thinking (or, at times, glowering—a facial expression I perfected as a youngster), as New England becomes more densely populated, as our forests are carved into by developers, we need to pretend that we're more isolated than we are; we need to bolster up the illusion that we don't have all these neighbors swarming about.

There's nothing really, fundamentally wrong with being friendly. I decided I would test out Midwestern behavior in Connecticut for practice. I go for a lot of walks. On my walks, I try, now, to say hello to everyone I encounter. The only people who seem to appreciate it are the residents of the assisted living homes on my block. They are expert porch-sitters, so I get the opportunity to say hello to each set several times per day. They are, almost without exception, enthusiastically friendly in return.

5 comments:

This is wonderful, and true. What a thoughtful mind you have, sweetie.

PS I didn't friggin' "IMAGINE" anything--those planes WERE sent by the president, and McPherson IS the absolute center of the continental US of friggin' A, if not the world, or, heckfire, the universe.

I'll have to revise the essay to be more representative of your [ahem] reality, then.

I have noticed that even just outside New England's boarders, this phenomenon changes. I travel for my job a bit, and was surprised by how many strangers said hello to me even just over in New Jersey, or the Hudson Valley. I like when I hear it, but I am less likely to initiate. That's my Boston area upbringing I suppose. I've also been trying to break it.

Hello, betsy q. bramble. Thanks for reading.

I certainly agree that it's harder to initiate greeting a stranger...maybe it's imagining that strangers expect you to also be initiating contact that made me so nervous.

Post a Comment