by Jillian Vento

My parents’ house, the same house in which I grew up, is situated half way up the highest hill in our town. We lived in the midst of a dense deciduous forest. Patrick and I would play in the woods or down the hill in the stream that went beneath (and sometimes flooded above) our driveway.

The driveway itself is an old Town road. Woodland cuts North up through the trees and across the hill on which my house sits, snug amongst the Sugar Maples. The old Woodland continues beyond my house, gets lost and obscured in the woods a bit, and then emerges as an active, if unpaved road several miles out.

When we were young, Pat and I (and, later, Nora) were sent outside a fair amount. We would meander our way through the woods, to the swamp or to the stream. We would wander up the hill to the cliffs. After some time, we would hear it: the simulated owl’s hoot that one parent or other would let out, expecting us to echo back. It was our honing mechanism.

The woods are filled with sounds. It’s a tightly packed euphony: trees that creak in winter under the weight of ice or snow, animals that scamper through last autumn’s dead leaves, wind through trees and over rocks, water carving its way down the hill, and the owls.

Even as a child I was enamored with the owls. When, in Twin Peaks, various characters warn the “the owls are not what they seem,” rather than feeling alarmed by that kind of sylvan scopophilia, I felt comforted by the idea that these birds could be nocturnal sentinels.

One of my father’s favorite tasks is filling the bird feeders in the yard and off the porch. After he’s funneled the feed into the containers – some of them wooden, some of them copper and glass, some plastic and wire mesh – he stands back on the porch and surveys the field. He points out the woodpeckers, the blue jays, the sparrows. He pelts the occasional squirrel with a snowball.

My father protects those precious creatures. I mean precious in the sense Catholics mean it when they talk about the precious body or the precious blood. I mean that material form that takes on the qualities of the miraculous. Birds.

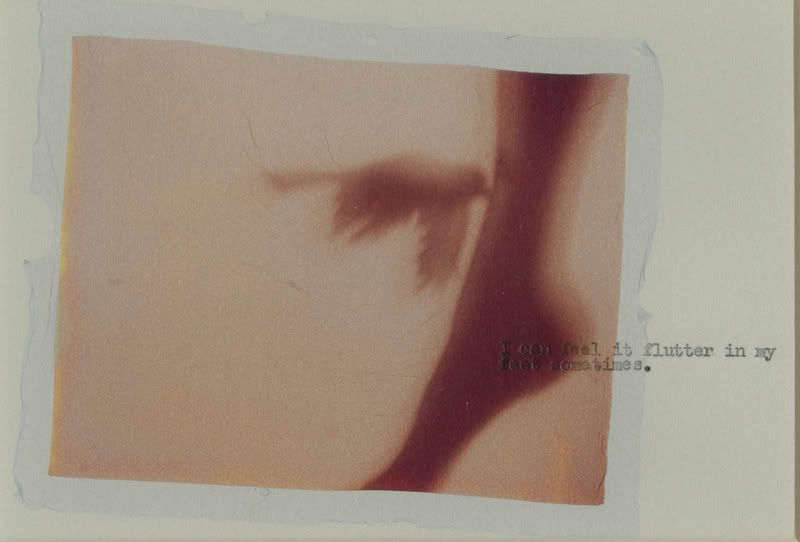

Impossibly crossed feet. Impossibly hollow bones. Impossibly delicate babies.

I suppose part of it started when we lived in the house on Storrs Road, by the lake. It was on the second floor of an early 19th-century farm house that had been converted in the 70s to apartments. We had a small porch and long stairway that we lined with flowers (a magnificent fuchsia that year) and tomatoes and basil. The sparrow built her nest in the eve of the small overhang that covered our doorway. In the mornings and evenings we would avoid opening the door very much at all so as not to scare her off. You would stand in the kitchen and elicit in me peal upon peal of laughter by imitating the babies.

It's still too sad to represent properly. After several days and no plaintive cries from the nest, I asked you to look in, to bury them somewhere. I couldn't even stand to look. And you did it for me.

I'm working up to something, here, but I can't just yet.